Chemists make device to destroy planet-warming methane pollution

It could slash a very potent greenhouse gas from sites such as livestock barns

By Laura Allen

Dairy barns. Hog farms. Rotting trash. What do they have in common? All release methane, an especially powerful planet-warming gas. Now, scientists have found a new method to quash that gas. The approach could slash emissions from places like livestock barns and landfills — and bring the planet one step closer to slowing global warming.

Methane is a carbon atom bound to four hydrogen atoms. A single molecule of it is 80 times better at trapping heat in the atmosphere than a molecule of carbon dioxide. That’s why cutting methane emissions is a key step to decarbonization — and cooling Earth’s climate.

Each methane molecule holds energy within its chemical bonds. If concentrated enough, methane can be used as fuel. In fact, natural gas is mostly methane. Burning it produces useful heat, plus carbon dioxide. But most methane pollution — about three-quarters — is far too dilute to be used as fuel.

A lot of this diffuse methane comes from livestock. Cow burps and rotting manure, for instance, pump out around a third of all the methane linked to human activities.

Microbes in cows’ digestive systems help them break down tough grasses and other plants. In the process, they produce methane that contributes to warming Earth’s atmosphere.

People have dreamed of pulling methane from the air to use as a resource, says Matt Johnson. He’s a chemist at the University of Copenhagen, in Denmark. But that hasn’t worked, largely due to its diffuse nature. “That’s one of the real problems with methane,” he says. If it’s not concentrated enough to burn, “it’s hard to know how to use it.”

Without a way to capture this methane, scientists have turned their attention to destroying it.

“I invented a method of cleaning air that was able to remove a lot of air pollution,” says Johnson. “People were asking me whether this couldn’t be used to destroy methane,” he says. Unfortunately, it couldn’t.

Methane is stable. It doesn’t dissolve well in water or stick to filters. So many of the traditional ways to clean air don’t work on methane, Johnson explains. Instead, he looked to see if he could mimic one way that nature breaks apart methane high in the atmosphere.

And his team has now made this work.

The methane destroyer

When sunlight hits naturally occurring chlorine (Cl2) in the air, it splits the molecule. This creates two atoms, each with an unpaired electron. They are known as chlorine radicals (Cl·). These radicals are very reactive. They even react with stable methane molecules, breaking them down. But since there are relatively few chlorine radicals around, this natural process tends to eliminate only a small portion of the methane in air.

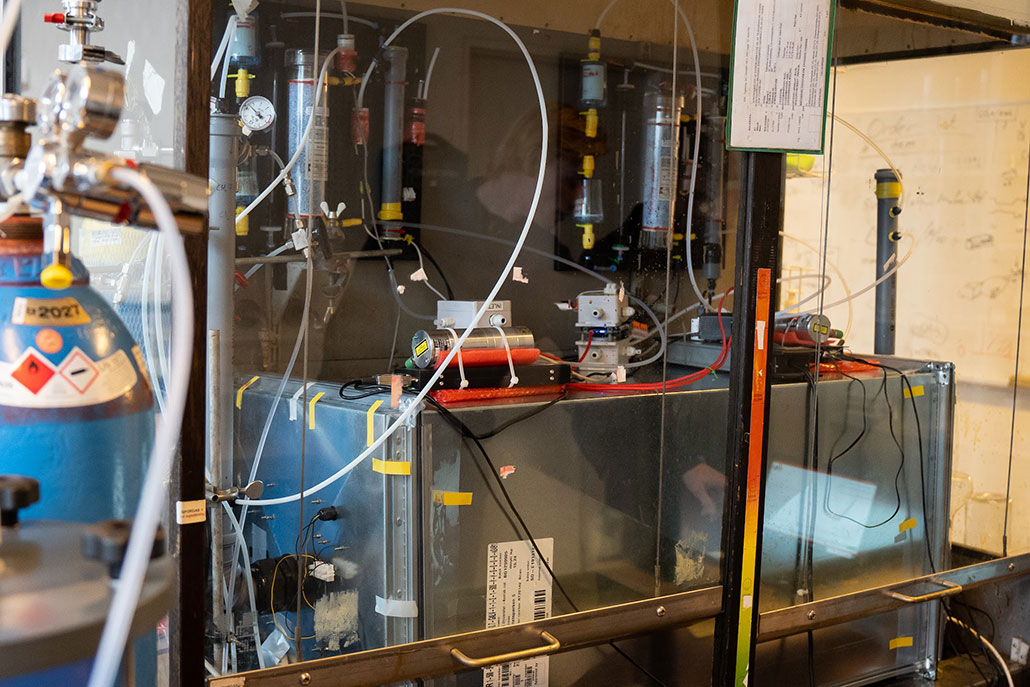

Here’s a test chamber used to break down methane. To start the process, the device pumps in methane, air and chlorine gas.HUGO RUSSELL AND MORTEN KROGSBØLL

Here’s a test chamber used to break down methane. To start the process, the device pumps in methane, air and chlorine gas.HUGO RUSSELL AND MORTEN KROGSBØLLJohnson and his team have now designed a device to do the same thing. To speed methane’s removal, they boost the concentration of chlorine.

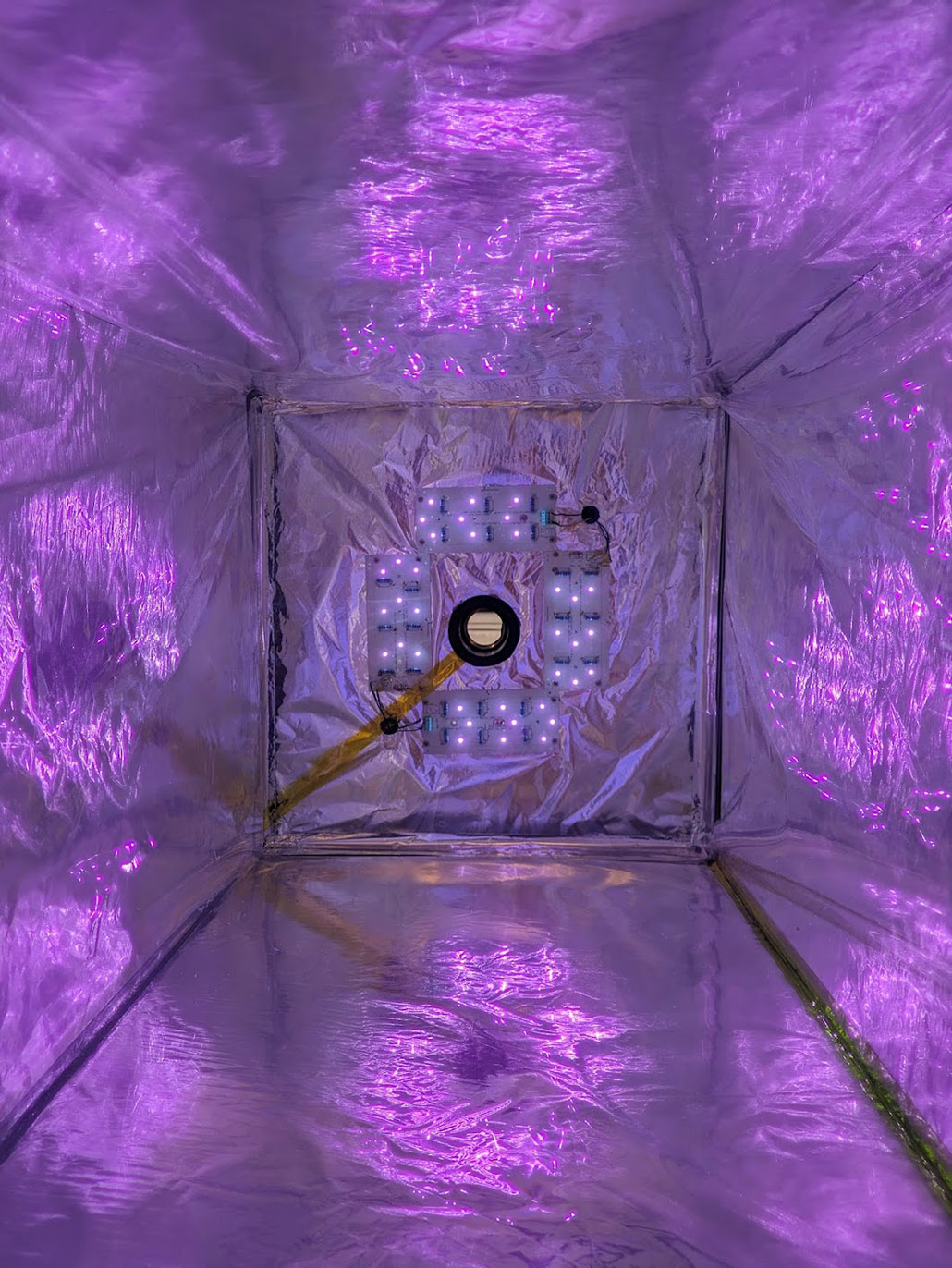

Inside the new test chamber, LED bulbs shine UV light, which reflects off the walls and onto chlorine molecules. This splits the chlorine into reactive radicals. These atoms go on to break apart methane into carbon dioxide and hydrogen.HUGO RUSSELL AND MORTEN KROGSBØLL

Inside the new test chamber, LED bulbs shine UV light, which reflects off the walls and onto chlorine molecules. This splits the chlorine into reactive radicals. These atoms go on to break apart methane into carbon dioxide and hydrogen.HUGO RUSSELL AND MORTEN KROGSBØLLThey start with a unit normally used to disinfect home swimming pools. This device uses electricity to split sodium chloride (NaCl) — or table salt — into Cl2 gas and sodium. The researchers then pump the chlorine gas into a steel chamber along with air and methane.

Inside the chamber, LED bulbs shine ultraviolet light onto the chlorine gas. This light breaks those gas molecules into chlorine radicals.

The reactive chlorine radicals cleave off a hydrogen atom from each methane molecule (CH4). This leaves a methyl radical (CH3). It reacts with oxygen in the air, creating two byproducts: carbon monoxide (CO) and CO2. (Since CO2 is a less powerful greenhouse gas than methane, it’s safer to release into outdoor air.)

In the test chamber, the chlorine radicals react with methane’s hydrogen atoms to make hydrochloric acid (HCl). A filter on the outlet of the chamber catches the acid so that its chlorine can be reused. (None of the chlorine gas nor acid leave the device.)

In tests, the new device removed 58 percent of the methane from the air. The team shared its findings online November 20 in Environmental Research Letters.

Future versions

From the outside, the test chamber resembles a piece of steel ductwork that’s one meter (39 inches) long. The researchers plan to build a larger version — one built into a 12-meter (40-foot) long shipping container — for testing at a farm next summer. They’ll adapt the barn’s ventilation system to blow methane-laden air from the animals into the device. Johnson expects this larger system will more efficiently destroy methane than his little lab setup did.

“The technology seems very promising,” says Tingzhen Ming. He’s an engineer at Wuhan University of Technology in China. He, too, works on controlling methane.

Ming sees this Danish system as well suited to fill a gap. It can tackle diffuse methane emitted from places like livestock barns or landfills. What it’s not well suited for, he notes, are more concentrated emissions. It also won’t work for methane emitted into wide open areas, such as a rice field or the Arctic (by thawing permafrost).

Plus, one byproduct of the new device could be useful on its own: hydrogen. This gas can power a fuel cell to make electricity. In the future, Johnson’s team wants to harness that hydrogen power. It’s a way to use some of the energy in methane, he says. Another green upgrade, Johnson says, would be to directly capture the CO2 leaving the new system.

These three steps — slashing methane, directly capturing carbon and harnessing hydrogen for use as an energy source — could go a long way to decarbonizing meat and dairy production, Johnson says.

But globally, notes Ming, we have to do more than address methane emissions from barns. Countries need to make it a priority to cut the release of both CO2 and methane, he says.

Power Words

atmosphere: The envelope of gases surrounding Earth, another planet or a moon.

atom: The basic unit of a chemical element. Atoms are made up of a dense nucleus that contains positively charged protons and uncharged neutrons. The nucleus is orbited by a cloud of negatively charged electrons.

bond: (in chemistry) A semi-permanent attachment between atoms — or groups of atoms — in a molecule. It’s formed by an attractive force between the participating atoms. Once bonded, the atoms will work as a unit. To separate the component atoms, energy must be supplied to the molecule as heat or some other type of radiation.

carbon dioxide: (or CO2) A colorless, odorless gas produced by all animals when the oxygen they inhale reacts with the carbon-rich foods that they’ve eaten. Carbon dioxide also is released when organic matter burns (including fossil fuels like oil or gas). Carbon dioxide acts as a greenhouse gas, trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere. Plants convert carbon dioxide into oxygen during photosynthesis, the process they use to make their own food.

carbon monoxide: A toxic gas whose molecules include one carbon atom and one oxygen atom. (The “mono” in “monoxide” is a prefix from Greek that means “one”.) One common source: fossil-fuel burning.

chemical bonds: Attractive forces between atoms that are strong enough to make the linked elements function as a single unit. Some of the attractive forces are weak, some are very strong. All bonds appear to link atoms through a sharing of — or an attempt to share — electrons.

chlorine: A chemical element with the scientific symbol Cl. It is sometimes used to kill germs in water. Compounds that contain chlorine are called chlorides.

climate: The weather conditions that typically exist in one area, in general, or over a long period.

concentration: (in chemistry) A measurement of how much of one substance has been dissolved into another.

dairy: Containing milk or having to do with cows or milk. Or a building or company in which milk is prepared for distribution and sale.

diffuse: adj.) To be spread out thinly over a great area; not concise or concentrated. (v) To spread light or to broadly release some substance through a liquid (such as water or air) or through some surface (such as a membrane).

dilute: To make something thinner or less concentrated by adding a liquid to it.

disinfect: To clean an area by killing dangerous infectious organisms, such as disease-causing bacteria.

dissolve: To turn a solid into a liquid and disperse it into that starting liquid. (For instance, sugar or salt crystals, which are solids, will dissolve into water. Now the crystals are gone and the solution is a fully dispersed mix of the liquid form of the sugar or salt in water.)

electricity: A flow of charge, usually from the movement of negatively charged particles, called electrons.

electron: A negatively charged particle, usually found orbiting the outer regions of an atom; also, the carrier of electricity within solids.

element: A building block of some larger structure. (in chemistry) Each of more than one hundred substances for which the smallest unit of each is a single atom. Examples include hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, lithium and uranium.

engineer: A person who uses science and math to solve problems. As a verb, to engineer means to design a device, material or process that will solve some problem or unmet need.

filter: (n.) Something that allows some materials to pass through but not others, based on their size or some other feature. (v.) The process of screening some things out on the basis of traits such as size, density, electric charge. (in physics) A screen, plate or layer of a substance that absorbs light or other radiation or selectively prevents the transmission of some of its components.

fuel cell: A device that converts chemical energy into electrical energy. The most common fuel is hydrogen, which emits only water vapor as a byproduct.

global warming: The gradual increase in the overall temperature of Earth’s atmosphere due to the greenhouse effect. This effect is caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons and other gases in the air, many of them released by human activity.

green: (in chemistry and environmental science) An adjective to describe products and processes that will pose little or no harm to living things or the environment.

greenhouse gas: A gas that contributes to the greenhouse effect by absorbing heat. Carbon dioxide is one example of a greenhouse gas.

hydrochloric acid: A strong (potent) and corrosive acid formed when hydrogen chloride gas dissolves into water. The human gut produces a dilute solution of this to break down foods.

hydrogen: The lightest element in the universe. As a gas, it is colorless, odorless and highly flammable. It’s an integral part of many fuels, fats and chemicals that make up living tissues. It’s made of a single proton (which serves as its nucleus) orbited by a single electron.

landfill: A site where trash is dumped and then covered with dirt to reduce smells. If they are not lined with impermeable materials, rains washing through these waste sites can leach out toxic materials and carry them downstream or into groundwater. Because trash in these facilities is covered by dirt, the wastes do not get ready access to sunlight and microbes to aid in their breakdown. As a result, even newspaper sent to a landfill may resist breakdown for many decades.

LED: (short for light emitting diode) Electronic components that, as their name suggests, emit light when electricity flows through them. LEDs are very energy-efficient and often can be very bright. They have lately been replacing conventional lights for home and commercial lamps.

livestock: Animals raised for meat or dairy products, including cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens and geese.

manure: Feces, or dung, from farm animals. Manure can be used to fertilize land.

methane: A hydrocarbon with the chemical formula CH4 (meaning there are four hydrogen atoms bound to one carbon atom). It’s a natural constituent of what’s known as natural gas. It’s also emitted by decomposing plant material in wetlands and is belched out by cows and other ruminant livestock. From a climate perspective, methane is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide is in trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere, making it a very important greenhouse gas.

molecule: An electrically neutral group of atoms that represents the smallest possible amount of a chemical compound. Molecules can be made of single types of atoms or of different types. For example, the oxygen in the air is made of two oxygen atoms (O2), but water is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H2O).

natural gas: A mix of gases that developed underground over millions of years (often in association with crude oil). Most natural gas starts out as 50 to 90 percent methane, along with small amounts of heavier hydrocarbons, such as propane and butane.

permafrost: Soil that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years. Such conditions typically occur in polar climates, where average annual temperatures remain close to or below freezing.

physical: (adj.) A term for things that exist in the real world, as opposed to in memories or the imagination. It can also refer to properties of materials that are due to their size and non-chemical interactions (such as when one block slams with force into another).

quash: To completely suppress, destroy, neutralize or extinguish.

radical: (in chemistry) A molecule having one or more unpaired outer electrons. Radicals readily take part in chemical reactions. The body is capable of making radicals as one means to kill cells, and thereby rid itself of damaged cells or infectious microbes.

reactive: (in chemistry) The tendency of a substance to take part in a chemical process, known as a reaction, that leads to new chemicals or changes in existing chemicals.

salt: A compound made by combining an acid with a base (in a reaction that also creates water). The ocean contains many different salts — collectively called “sea salt.” Common table salt is a made of sodium and chlorine.

sodium: A soft, silvery metallic element that will interact explosively when added to water. It is also a basic building block of table salt (a molecule of which consists of one atom of sodium and one atom of chlorine: NaCl). It is also found in sea salt.

system: A network of parts that together work to achieve some function. For instance, the blood, vessels and heart are primary components of the human body's circulatory system. Similarly, trains, platforms, tracks, roadway signals and overpasses are among the potential components of a nation's railway system. System can even be applied to the processes or ideas that are part of some method or ordered set of procedures for getting a task done.

technology: The application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry — or the devices, processes and systems that result from those efforts.

ultraviolet: A portion of the light spectrum that is close to violet but invisible to the human eye.

ventilation: A system that supplies a room with fresh air or processes that move air around and between different rooms.

CITATIONS

Journal: M. Krogsbøll, H.S. Russell and M.S. Johnson. A high efficiency gas phase photoreactor for eradication of methane from low-concentration sources. Environmental Research Letters. Vol. 19, January 2024, p. 014017. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ad0e33.

Journal: S. Abernethy, M.I. Kessler and R.B. Jackson. Assessing the potential benefits of methane oxidation technologies using a concentration-based framework. Environmental Research Letters. Vol. 18, September 2023, p. 094064. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/acf603.

Report: United Nations Environment Programme and Climate and Clean Air Coalition. Global methane assessment: Benefits and costs of mitigating methane emissions. 2021. ISBN: 978-92-807-3854-4.

Journal: M.S. Johnson et al. Gas-phase advanced oxidation for effective, efficient in situ control of pollution. Environmental Science and Technology. Vol. 48, June 23, 2014, p. 8768. doi: 10.1021/es5012687.

Source: [ ScienceNewsExplores ]

Note: [Content may be edited for style and length.]