Too much noise can harm far more than our ears

Besides damaging hearing, it can also disrupt learning, stress us out and more

By

|

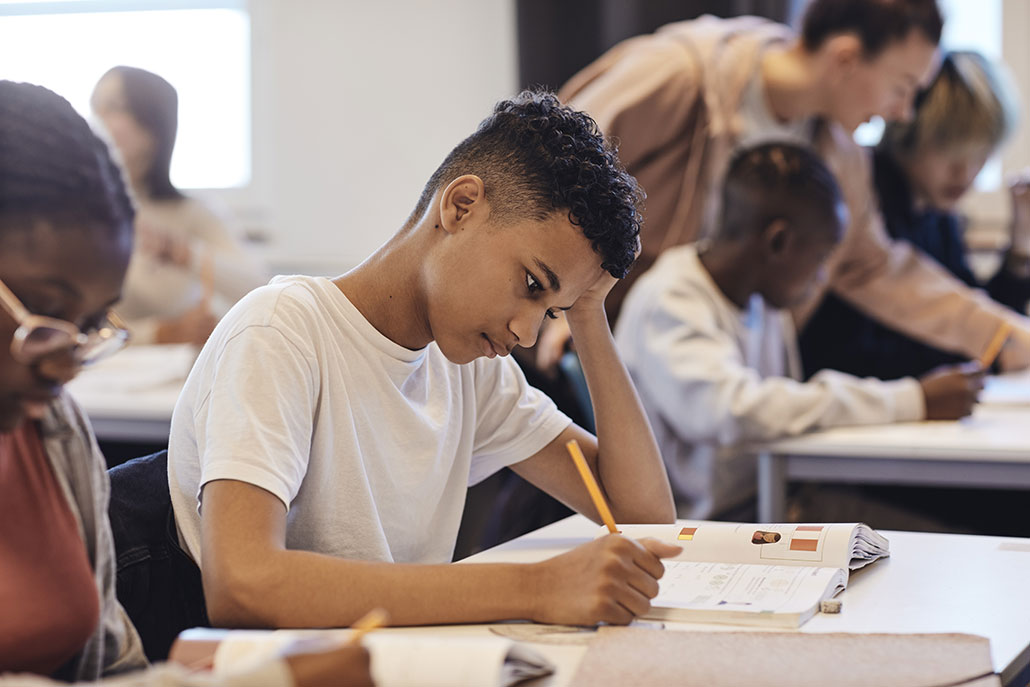

Noise can harm your ears, brain — and ability to learn.

AARONAMAT/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS |

Sophie Balk loved to dance. She used to take part in dance competitions, doing West Coast Swing — a bouncy, twirly partner dance. At first, the music’s volume didn’t bother her. But after a while, her ears began to hurt. Sometimes her ears were ringing as she left the dance club. Balk eventually developed a hearing disorder called tinnitus — a nonstop ringing in her ears.

“When we go out into the sun, we protect our skin from sunburn by covering it up or wearing sunscreen,” Balk says. But, she notes, “We don’t think about protecting our hearing in the same way.” Balk is a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital at Montefiore in New York City. She now teaches other doctors about the risks posed by noise.

Loud sounds are a major environmental source of health problems. In some places, it ranks second only to air pollution, the World Health Organization notes.

When it comes to noise, hearing problems are the best known risk. But emerging research is uncovering how noise also affects the brain. It’s showing how even sounds that don’t trigger hearing loss can still harm us. Sounds from cars, lawnmowers and other everyday sources are being linked to stress, poor sleep, learning problems — even heart disease.

Clearly, noise is far more than just a pesky irritant.

How noise harms hearing

We’ve known for centuries that too much noise can cause hearing loss, says Richard Neitzel. He works at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Some 200 years ago, accounts described blacksmiths who developed hearing loss from their constant hammering of metal.

Neitzel is an industrial hygienist, someone who studies how to keep people healthy at work. Most of what we know about noise and health, he says, comes from studying workers in loud jobs.

Very loud sounds can damage tiny cells deep inside our ears. Called hair cells, they pick up sound vibrations from the air. Loud sounds also can damage the auditory nerve that carries signals from those hair cells to the brain.

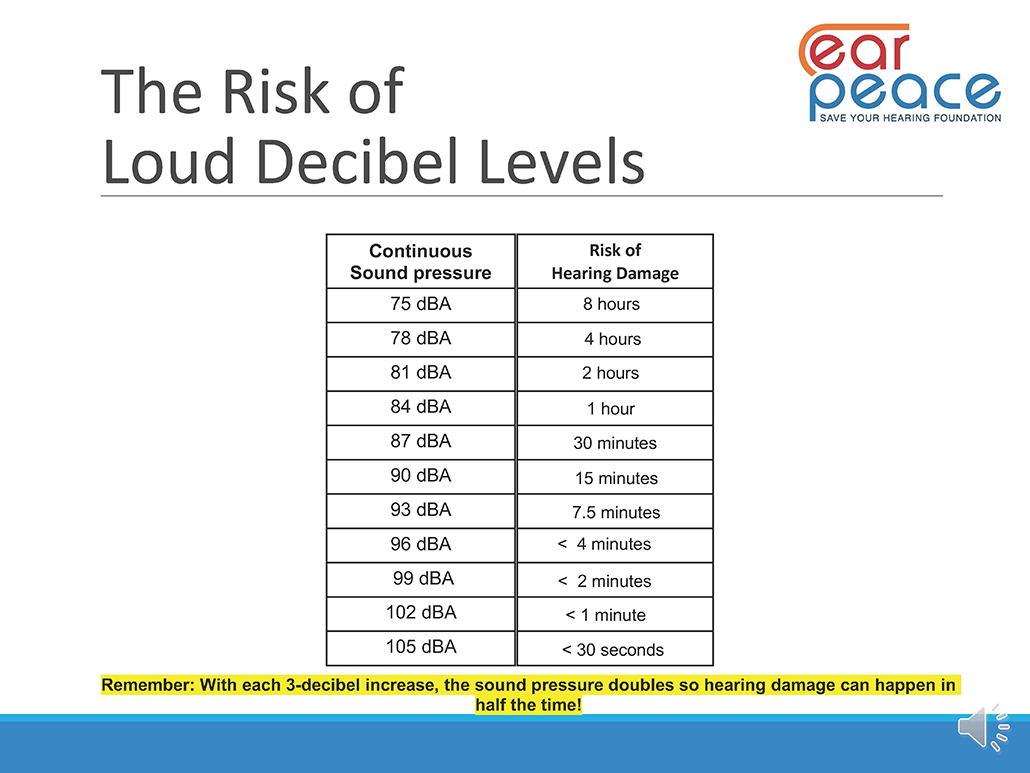

The risks posed by any given sound will depend on its volume, its pitch and how long it lasts. The softest sound we can hear is termed zero decibels. We typically converse at around 60 decibels. Gas-powered lawn mowers roar at some 95 decibels.

Audible sounds between 100 and 120 decibels can start to feel painful. But even moderately loud sound — such as busy street traffic — can cause harm if we hear it for hours.

Today, about one in every eight kids and teens have permanent hearing damage from being exposed to too much noise, says the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To avoid hearing loss, research suggests, kids shouldn’t be exposed to sounds louder than 75 decibels. That’s about as loud as a vacuum cleaner.

But there’s more to how we experience sound than just the decibel levels reaching our ears. New research is exploring how the brain makes sense of what we hear — and why some sounds feel unpleasant, even when they’re not dangerously loud.

Noise and the brain

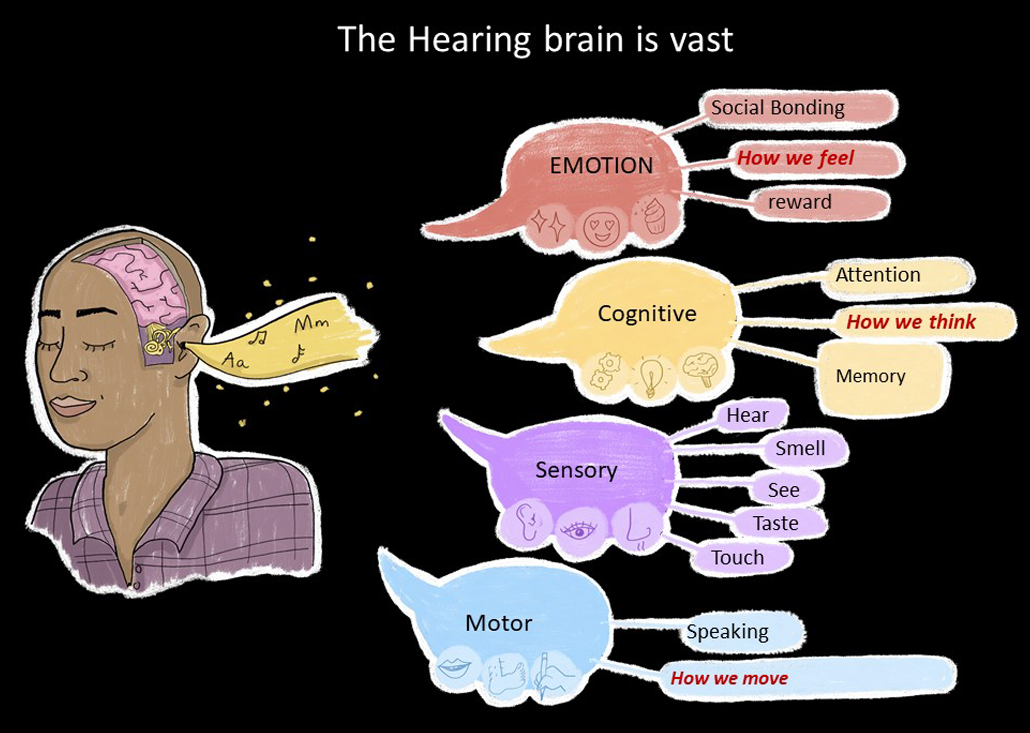

“Our ears capture sound, but we hear with our brains,” explains Wei Sun. He’s an audiology researcher at the University at Buffalo in New York. The auditory nerve relays sound signals from the ears to our brain. Nerve cells in the brain then process that input by sending each other electrical signals. That electrical activity gives rise to what we experience as sound.

Nina Kraus is among researchers taking a close look at this brain activity. An auditory neuroscientist, she works at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. Kraus also wrote the book Of Sound Mind: How our Brain Constructs a Meaningful Sonic World.

For their studies, Kraus and her colleagues placed caps embedded with electrodes on people’s heads. Those caps pick up brain activity as the ears detect sound. In this way, researchers were able to map parts of the brain involved in listening to and interpreting sounds. Those regions include ones that play a role in thinking, moving, feeling and sensing.

“There’s a lot that goes on in the brain when processing a sound,” notes Laurie Heller. “You’re deciding whether or not you like the sound, whether to pay attention to or ignore the sound, what to do with that information.”

Heller is a psychologist who studies how the brain interprets sound. She works at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa. Her work has explored why some sounds register as unpleasant noise. For instance, a bubbling brook might feel like a peaceful sound — even when it’s as loud as an air conditioner that seems like an annoying racket.

In one experiment, her team used a sound effect called a vocoder. It slightly changed some of the properties of common sounds. Then the team asked people to guess the source of each tweaked sound. Listeners also rated how they felt about it. Some sounds were pleasant, such as a flowing stream. Others were unpleasant, like a drink being slurped.

It appears that how people feel about a sound can depend on what they think caused it, Heller says. When people misidentified a neutral sound as having a negative source, they rated it as less pleasant. For example, the sound of a sink draining is neutral. But people rated it unpleasant or even disgusting when they thought it was the sound of someone slurping a drink. Meanwhile, people felt better about sounds they thought came from a neutral or positive source.

“Feeling negatively about the event that caused the sound is the most important predictor of its unpleasantness,” Heller finds.

People with hearing loss may have a harder time identifying the true cause of a sound. And that could put them at higher risk of judging what they hear as unpleasant.

Heller also works with people who have a condition known as misophonia (Mee-zoh-FOH-nee-uh). It can make people feel angry or distressed when they hear common sounds — ones that others may not even notice (such as someone chewing or breathing). Studying their brains may offer insight into why any of us experience some things as noise, Heller says.

Misophonia appears to arise from how some brains interpret sounds. In affected people, certain sounds trigger a lot more activity in a part of the brain that alerts us to important things. That region also engages our emotions.

This leaves these folks “paying a lot more attention to sounds they find unbearable,” Heller says.

Better understanding this mental connection could not only lead to new treatments for misophonia, but also tell us more about how the brain processes sound in all of us. That’s key, because other research is revealing that exposure to too much unwanted sound — what we define as noise — can harm the brain in several ways.